Finding motivation in helping others

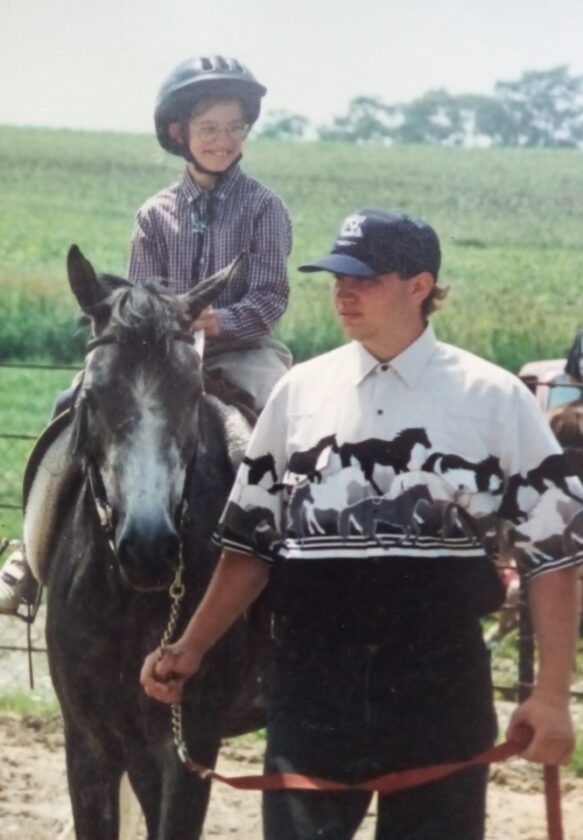

Simon leads horses for riders with disabilities.

When I agreed to build Centaur Stride, a therapeutic horseback riding facility, part of my motivation was deeply personal. I wanted to create a place where teens felt safe and like they belonged. Centaur Stride was not created only as an adjunct to physical therapy for children with physical disabilities, but also for those who had unseen or undiagnosed challenges.

My son was 15. I imagined teens volunteering together, finding connection through shared work and gentle horses.

What do I know about autism? Let’s go back 49 years.

My son cried endlessly, day and night. Doctors called it “colic.” They said he was allergic to breast milk, the reason for his “failure to thrive.” Nothing calmed him. No one knew about sensory disorders then.

Separation anxiety was fierce. Even eating was a daily challenge. He had frequent sinus infections, fevers treated with antibiotics, constant stomach aches and irritable bowel. He had “soft neurological signs”, they called them.

In school, he had an IEP under the label “Emotionally Disturbed” because he would shut down often, silently withdrawing when demands became overwhelming. They wanted to fail him even in kindergarten.

Writing was illegible. He squeezed the pencil so hard his fingers would cramp, and he would say that he couldn’t feel his fingers. Speaking didn’t come easily either; he rarely initiated and often froze when called on in class. One teacher even wrote on his report card, “Better to leave well enough alone.”

He was bullied often, until his younger sister, three years his junior, was old enough to intervene. She had “influential friends,” and word spread quickly that he was off limits. The bullying lessened, but the loneliness did not.

He was an auditory learner with a quick mind in a system that measured intelligence by written and verbal expression. Around that time, emotional intelligence, or EQ, began making headlines as a predictor of success. His EQ was far below average, and stagnant.

Rewards and punishments meant nothing; helping others was his only motivator.

When we started Centaur Stride, helping to make that happen made him feel important. It helped to uncover his strengths, when his brain could work in an atmosphere that didn’t judge his differences, and made him finally feel like he was enough, just as he was.

He once said, “Mom, I thought volunteering meant you did something when you wanted to.” It was a sincere statement, without sarcasm, questioning his understanding of a volunteer, and his unpaid role there, when others were getting paid.

Change arrived. A new instructor, and new methods. He couldn’t adapt to change, and his sense of belonging turned quickly into “unwelcome interference”.

My son’s intellectual abilities were strong, but emotionally he was easily wounded. After he was out of school, I realized how ill-prepared he was for any real-world expectations. My dream remained of a place where there was social support that could make someone functional and accepted regardless of differences, a “utopia” within a community, that would branch out to integrate with the community, with enough help until something became routine and familiar, but still provide a safe place within.

Bullies are not always kids at school. They are also employers, co-workers, health professionals, and people anywhere and everywhere. In the real world, there wasn’t anybody to protect him and he couldn’t defend himself. He was often in what is called “Defense Mode”, which is his way to shut down while trying to remain somewhat functional. Parents of children with autism know this scenario well. It is when you try to push your child to fit into a place where they are not wanted or welcomed. They know it.

Now, as my son grows older, he progressively retreats further into isolation. He has always existed in that invisible gap, too “high functioning”, yet too challenged to navigate life independently. And until two years ago, still undiagnosed, meaning no services or income.

Robin Williams once said, “I used to think the worst thing in life was to end up all alone. It’s not. The worst thing in life is to end up with people who make you feel all alone.” That quote captures the quiet ache of so many on the spectrum, and the people who love them. Present, yet apart; visible, yet unseen. Inclusion, when superficial, is just another form of isolation.

Over the years, I’ve attended many seminars on autism and sensory processing. I’ve worked with many children across the spectrum, each unique. I’ve witnessed meltdowns, aggression, and, most beautifully, breakthroughs. Among all therapeutic approaches, one has consistently shown the most profound and lasting transformation: Therapeutic Horseback Riding.

There is something sacred in the bond between horse and human. The connection requires no words, just trust, rhythm, and breath. A horse senses emotion without judgment. Its calm presence invites stillness. The horse accepts without expectation, offering what humans often can’t: unconditional understanding.

Maybe the horse is the bridge between silence and communication, isolation and connection, while we humans are still learning how to coexist.

And perhaps that’s the greatest lesson my son, and the horses, have taught me: connection isn’t about conformity or fixing what’s different. It’s about presence. It’s about love and acceptance that endures even when life doesn’t seem fair. I still dream of a social “utopia” within the community, where everyone has a productive purpose and a feeling of belonging. What would that look like? I found such a place that just needs a few more changes to include people like my son, but even then, it would only take that one person to make him walk away from it. Sadly, he was taught in school to walk away as a coping strategy. That’s like teaching a guard dog only half of the training, leaving out when to attack and when not to. It’s too late for my son, but paving the way for those younger may still make a difference.

Claudia Monroe is co-founder and President of Centaur Stride.